One Pier Available For Lease

- July 8, 2017

Great news! We will have a pier available NOW. Pier rental is $575 per month and includes electric and internet. Contact us for more information. Experience Bortle 1 sky.

Great news! We will have a pier available NOW. Pier rental is $575 per month and includes electric and internet. Contact us for more information. Experience Bortle 1 sky.

Great news! We will have a pier available on August 1st. Pier rental is $650 per month and includes electric and internet. Contact us for more information. Experience Bortle 1 sky.

Maria Mitchell (1818-1889)

Astronomer

Growing up in the whaling town of Nantucket, Massachusetts Mitchell grew up learning about the stars and navigation. She could rate the chronometers for whaling ships and plot the movements of the planets.

In 1847, her discovery of a comet invisible to the naked eye won her international fame and a medal from the king of Denmark. After that, she went to work for the U.S. Nautical Almanac Office to compute ephemeredes of the planet Venus.

When Vassar College was founded in 1865, she joined the faculty as a professor of astronomy and director of the college observatory. She became the first woman elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and founded the Association for the Advancement of Women in 1873, chairing the Committee on Women’s Work in Science until her death.

She studied at Cambridge as an undergraduate but was not awarded a degree because the university didn’t grant degrees to women at that time. After meeting Harlow Shapley, the Director of the Harvard College Observatory, who had just begun began a graduate program in astronomy, she left England for the United States in 1923.

Payne-Gaposchkin became the first person to earn a Ph.D. in astronomy from Radcliffe (now part of Harvard). By studying the spectra of stars, Payne-Gaposchkin determined that hydrogen and helium were the most abundant elements in stars. She was the first woman to receive the rand of full professor at Harvard and also the first woman chairperson of a department at Harvard University.

“Let’s grant that the stars are scattered through space, hither and yon. But how hither, and how yon? To the unaided eye the brightest stars are more than a hundred times brighter than the dimmest. So the dim ones are obviously a hundred times farther away from Earth, aren’t they?

Nope.

That simple argument boldly assumes that all stars are intrinsically equally luminous, automatically making the near ones brighter than the far ones. Stars, however, come in a staggering range of luminosities, spanning ten orders of magnitude ten powers of ten. So the brightest stars are not necessarily the ones closest to Earth. In fact, most of the stars you see in the night sky are of the highly luminous variety, and they lie extraordinarily far away.

If most of the stars we see are highly luminous, then surely those stars are common throughout the galaxy.

Nope again.

High-luminosity stars are the rarest. In any given volume of space, they’re outnumbered by the low-luminosity stars a thousand to one. It’s the prodigious energy output of high-luminosity stars that enables you to see them across such large volumes of space.”

― Neil deGrasse Tyson, Death by Black Hole: And Other Cosmic Quandaries

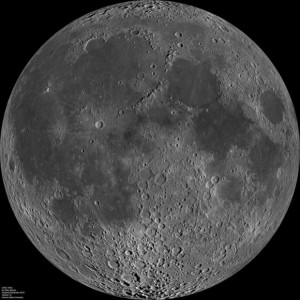

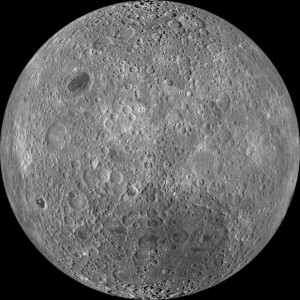

When spacecraft first transmitted the images of the moon’s far side to Earth, we saw the lunar farside lacks the large dark areas called maria, or seas. Why?

Composite image of the lunar nearside taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter in June 2009. Note the presence of dark areas – called maria by astronomers – on this side of the moon. Image via NASA

Composite image of the lunar farside – the side that always faces away from Earth – taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter in June 2009. Note the absence of large dark areas. Image via NASA

The dark maria or seas – large flat areas of basalt on the moon’s near side – are sometimes referred to as the man in the moon. No such features exist on far side of the moon. Why are there dark maria on the moon’s near side, but not far side? Penn State astrophysicists think they have the answer. They believe that the absence of maria, which is due to a difference in crustal thickness between the near side of the moon and the far side, is a consequence of how the moon originally formed. The researchers reported their results in the June 9 Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Jason Wright, assistant professor of astrophysics at Penn State, said:

I remember the first time I saw a globe of the moon as a boy, being struck by how different the farside looks. It was all mountains and craters. Where were the maria? It turns out it’s been a mystery since the 1950s.

This mystery – called the Lunar Farside Highlands Problem by astronomers – dates back to 1959, when the Soviet spacecraft Luna 3 transmitted the first images of the dark side of the moon back to Earth. Researchers immediately noticed that fewer maria on the portion of the moon that always faces away from Earth.

The Penn State astronomers looked back to the formation of the moon for their ideas on why one side of the moon has maria, and the other doesn’t. The general consensus on the moon’s origin is that it probably formed shortly after the Earth and was the result of a Mars-sized object hitting Earth with a glancing, but devastating impact. This Giant Impact Hypothesis suggests that the outer layers of the Earth and the object were flung into space and eventually formed the moon.

Shortly after the giant impact, the Earth and the moon were very hot, said researchers. The Earth and the impact object did not just melt; parts of them vaporized, creating a disk of rock, magma and vapor around the Earth.

The geometry was similar to the rocky exoplanets recently discovered very close to their stars, said Wright. The moon was 10 to 20 times closer to Earth than it is now, and the researchers found that it quickly assumed a tidally locked position with the rotation time of the moon equal to the orbital period of the moon around the Earth. The same real estate on the moon has probably always faced the Earth ever since. Tidal locking is a product of the gravity of both objects.

The moon, being much smaller than Earth cooled more quickly. Because the Earth and the moon were tidally locked from the beginning, the still hot Earth – more than 2500 degrees Celsius – radiated towards the near side of the moon. The far side, away from the boiling Earth, slowly cooled, while the Earth-facing side was kept molten creating a temperature gradient between the two halves.

This gradient was important for crustal formation on the moon. The moon’s crust has high concentrations of aluminum and calcium, elements that are very hard to vaporize.

Aluminum and calcium would have preferentially condensed in the atmosphere of the cold side of the moon because the nearside was still too hot. Thousands to millions of years later, these elements combined with silicates in the moon’s mantle to form plagioclase feldspars, which eventually moved to the surface and formed the moon’s crust. The farside crust had more of these minerals and is thicker.

The moon has now completely cooled and is not molten below the surface. Earlier in its history, large meteoroids struck the nearside of the moon and punched through the crust, releasing the vast lakes of basaltic lava that formed the nearside maria that make up the characteristic man in the moon features.

Meanwhile, when meteoroids struck the farside of the moon, in most cases the crust was too thick and no magmatic basalt welled up, creating the dark side of the moon with valleys, craters and highlands, but almost no maria.

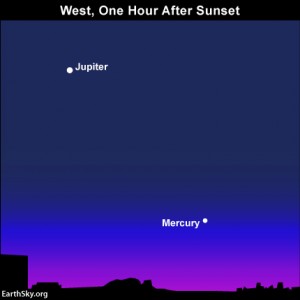

Mercury, the solar system’s innermost planet, orbits the sun inside of Earth’s orbit. Therefore, Mercury always stays close to the sun in Earth’s sky and is often lost in the sun’s glare. But Mercury reaches its greatest elongation – greatest angular distance – east of the sun on May 25, so this world can now be spotted low in the west-northeast as dusk ebbs into darkness. As always, binoculars help out with any Mercury quest.

The planet Jupiter is the first “star” to pop out after sunset. If you’re familiar with the star Regulus, you can draw an imaginary line from Regulus and past Jupiter to locate Mercury near the sunset point on the horizon. (See sky chart below.) Given a clear sky and unobstructed horizon, Mercury could be visible to the unaided eye about 60 to 90 minutes after sunset. If not, try binoculars.

Although Mercury shines more brightly than Regulus does, you might see Regulus first because it’s not as obscured by the glow of evening twilight. What is the ecliptic?

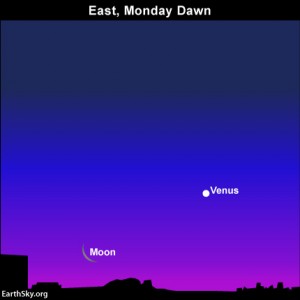

…and don’t forget the morning sky, which features the dazzling planet Venus and a thin waning crescent moon on Monday, May 26.

Setting times of the sun and Mercury in your sky

At an elongation of 23o Mercury lies far enough east of setting sun to stay out until the end of astronomical twilight (at mid-northern latitudes). By definition, astronomical twilight ends in the evening sky when the sun is 18o below the horizon. For reference, the sun’s diameter equals one-half degree, and your fist at an arm length approximates 10o.

Because Mercury is setting a maximum amount of time after sunset right now, this is your chance to catch Mercury low in the west at late dusk or nightfall. But don’t tarry when seeking this elusive yet surprisingly bright world, for Mercury – even now – follows the sun beneath the horizon around nightfall. At mid-northern latitudes, astronomical twilight ends nearly two hours after sunset, at about the same time that Mercury sets beneath the horizon.

End of nautical twilight and Mercury’s setting time in your sky

We should mention that the Northern Hemisphere enjoys the better view of this particular evening apparition of Mercury. That’s because the ecliptic – the pathway of the planets – hits the horizon at a steeper angle as the sun sets in the Northern Hemisphere sky.

Mercury stands higher over the horizon at sunset in Northern Hemisphere than at comparable latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere. For instance, at 40o north latitude – the latitude of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania – Mercury’s altitude at sunset is about 19o. In contrast, at 40o south latitude – the latitude of Wanganui, New Zealand – Mercury’s altitude is less than 11o at sunset.

No wonder Mercury sets more than 100 minutes after sunset at mid-northern latitudes but less than 80 minutes after sunset at mid-southern latitudes. The farther north you live, the later that Mercury sets after sunset; and the farther south you live, the sooner.

Although this evening apparition of Mercury favors the Northern Hemisphere, everyone worldwide has a reasonably good chance of catching Mercury after sunset right now. Look for Mercury above the sunset point on the horizon some 60 to 75 minutes after sunset.

Mercury might be visible to the unaided eye for another week or so, but binoculars always help out with your search for Mercury, the solar system’s innermost planet.

Bruce McClure EarthSky News

Good morning All!

SkyPi Observatory has been added to the Dark Sky Finder Map. The Site number is 4585. As you can see, we can boast some of the darkest skies in the U.S.

We had some fun last weekend testing the roof opening for both Alpha and Bravo buildings. Bravo is the second completed observatory housing 2 piers, almost identical to Alpha building. There are a few cosmetic items to complete as well as installing the steps going into the building. I hope you enjoy the video. We sure did!

[embedplusvideo height=”312″ width=”380″ editlink=”http://bit.ly/1h4nhaZ” standard=”http://www.youtube.com/v/gG6pnOOeVN8?fs=1″ vars=”ytid=gG6pnOOeVN8&width=380&height=312&start=&stop=&rs=w&hd=0&autoplay=0&react=1&chapters=¬es=” id=”ep5716″ /]

Hello! We are spending this weekend onsite. John, Bob, Kevin and Brian worked most of the day today framing the walls. They packed it in around 5:00 pm before the rain came. It didn’t rain much but there was a fairly good light show! Check out our pictures of today’s progress on the Phase 2 page. More to come tomorrow. Clear skies! Jan