Far side of the moon mystery solved

- June 15, 2014

When spacecraft first transmitted the images of the moon’s far side to Earth, we saw the lunar farside lacks the large dark areas called maria, or seas. Why?

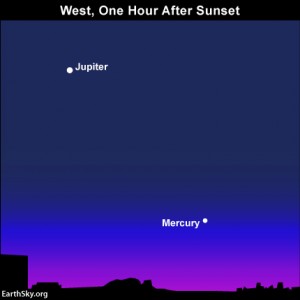

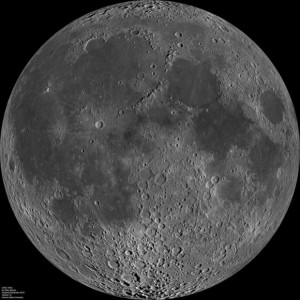

Composite image of the lunar nearside taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter in June 2009. Note the presence of dark areas – called maria by astronomers – on this side of the moon. Image via NASA

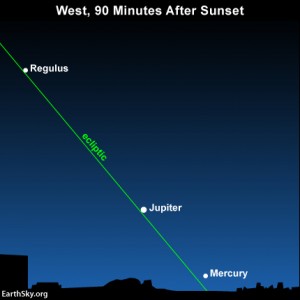

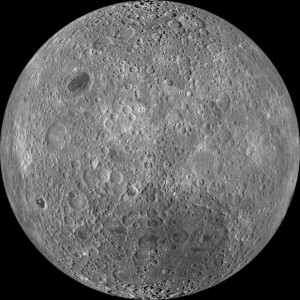

Composite image of the lunar farside – the side that always faces away from Earth – taken by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter in June 2009. Note the absence of large dark areas. Image via NASA

The dark maria or seas – large flat areas of basalt on the moon’s near side – are sometimes referred to as the man in the moon. No such features exist on far side of the moon. Why are there dark maria on the moon’s near side, but not far side? Penn State astrophysicists think they have the answer. They believe that the absence of maria, which is due to a difference in crustal thickness between the near side of the moon and the far side, is a consequence of how the moon originally formed. The researchers reported their results in the June 9 Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Jason Wright, assistant professor of astrophysics at Penn State, said:

I remember the first time I saw a globe of the moon as a boy, being struck by how different the farside looks. It was all mountains and craters. Where were the maria? It turns out it’s been a mystery since the 1950s.

This mystery – called the Lunar Farside Highlands Problem by astronomers – dates back to 1959, when the Soviet spacecraft Luna 3 transmitted the first images of the dark side of the moon back to Earth. Researchers immediately noticed that fewer maria on the portion of the moon that always faces away from Earth.

The Penn State astronomers looked back to the formation of the moon for their ideas on why one side of the moon has maria, and the other doesn’t. The general consensus on the moon’s origin is that it probably formed shortly after the Earth and was the result of a Mars-sized object hitting Earth with a glancing, but devastating impact. This Giant Impact Hypothesis suggests that the outer layers of the Earth and the object were flung into space and eventually formed the moon.

Shortly after the giant impact, the Earth and the moon were very hot, said researchers. The Earth and the impact object did not just melt; parts of them vaporized, creating a disk of rock, magma and vapor around the Earth.

The geometry was similar to the rocky exoplanets recently discovered very close to their stars, said Wright. The moon was 10 to 20 times closer to Earth than it is now, and the researchers found that it quickly assumed a tidally locked position with the rotation time of the moon equal to the orbital period of the moon around the Earth. The same real estate on the moon has probably always faced the Earth ever since. Tidal locking is a product of the gravity of both objects.

The moon, being much smaller than Earth cooled more quickly. Because the Earth and the moon were tidally locked from the beginning, the still hot Earth – more than 2500 degrees Celsius – radiated towards the near side of the moon. The far side, away from the boiling Earth, slowly cooled, while the Earth-facing side was kept molten creating a temperature gradient between the two halves.

This gradient was important for crustal formation on the moon. The moon’s crust has high concentrations of aluminum and calcium, elements that are very hard to vaporize.

Aluminum and calcium would have preferentially condensed in the atmosphere of the cold side of the moon because the nearside was still too hot. Thousands to millions of years later, these elements combined with silicates in the moon’s mantle to form plagioclase feldspars, which eventually moved to the surface and formed the moon’s crust. The farside crust had more of these minerals and is thicker.

The moon has now completely cooled and is not molten below the surface. Earlier in its history, large meteoroids struck the nearside of the moon and punched through the crust, releasing the vast lakes of basaltic lava that formed the nearside maria that make up the characteristic man in the moon features.

Meanwhile, when meteoroids struck the farside of the moon, in most cases the crust was too thick and no magmatic basalt welled up, creating the dark side of the moon with valleys, craters and highlands, but almost no maria.